< Previous / Next >

|

Article Index < Previous / Next > |

Translating Burgundy

- an explanation of the region and its wine styles

It is no secret that my desert island wine comes affixed with a label from

The best explanation (that I have) for the continued attraction to this exceedingly complex network of vineyards is that once you sample a superb bottle of Burgundy, nothing else seems to shine quite as bright. The challenge, however, is that these bottles are few and far between, and thus it becomes a quest to repeat something that arguably may never be duplicated.

I do not intend to present anything

pioneering in the way of ideas here, but rather I'd like to simplify the

technicalities that intimidate newcomers when confronted by a bottle of

The

taste of

The

taste of

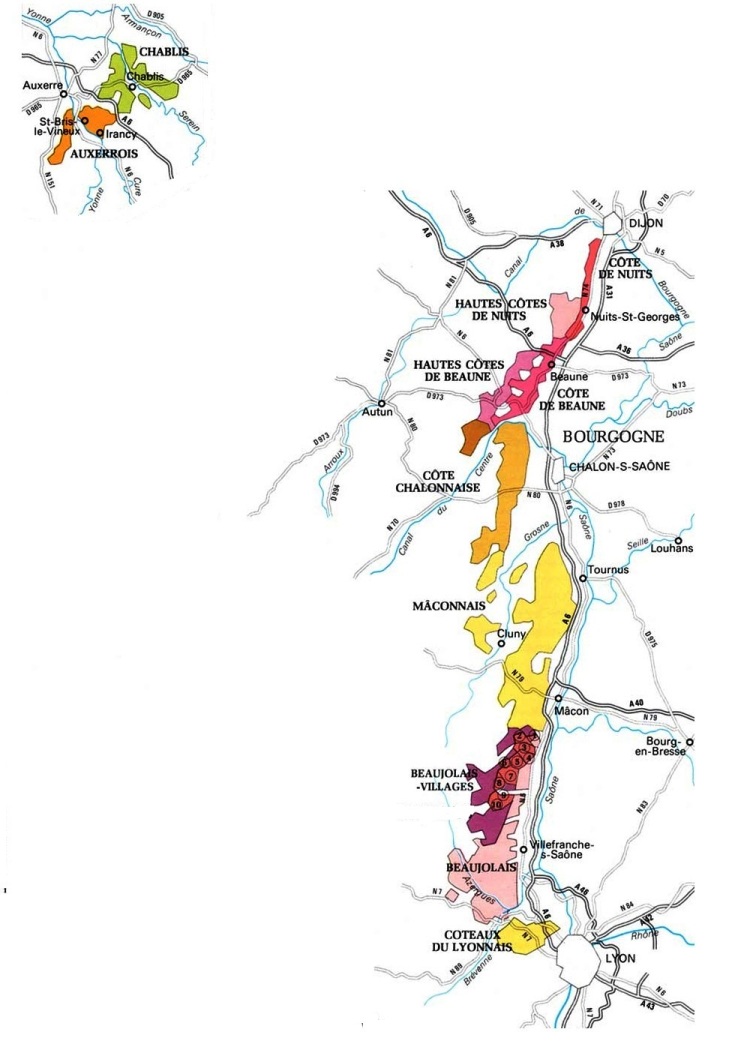

Further to the south again, the focus becomes rather intense, and as you enter

the famous Côte d’Or or ‘golden slope’ where richly complex Pinot Noir dominates

the vineyards of the Côte de Nuits. These unassuming vines are without

question the benchmark by which all Pinot is compared. As a rule, the red wine

begins to lighten in body as you travel south through the Côte d’Or into Beaune

where Pinot then takes a backseat to the delicately oaked and ever changing wine

of Chardonnay.

The Chalonnaise and Mâconnais follow and are home to more reasonably priced wine

of the same varieties, in addition to a hearty supply of lighter bodied wines

and crémant (sparkling) sourced from the Aligoté grape.

On the third Thursday of each November, the Beaujolais releases their fruity

Nouveau to a world of enthusiastic partygoers, but

Historically, each vineyard in the region was awarded a classification based upon its position on the hillside and resultant potential for ripening fruit. Typically, there are three tiers of vineyards: an upper exposure, the mid-slope, and lower flat associated with each village. The favourable climats or plots of vines are generally those found on the mid-slope with a southeastern exposure in any given village.

With some exceptions in Chablis and

• Village (better quality from a specific village or commune) 37.5%

• Premier Cru (better still) 10%

• Grand Cru (exceptional) 1.5%

Chablis has a similar hierarchy with the addition of Petit

Chablis below the Village level.

It goes without saying that as you ascend through the

hierarchy, the price increases (rather aggressively, I might add). Considering

the rarity and auction hammer prices at

The

complication of

The

complication of

Enter the négociant: Within the body of

To put the subject in perspective, the majority of

A few big name négociants to look for are: Louis Latour, Louis Jadot, Bouchard Père et Fils, Domaine Faiveley, Vincent Giradin, Domaine Roux Père et Fils, and Joseph Drouhin to list only a few.

That certainly does not imply that you should avoid the small

and more focussed production from individual ‘Domains’. Indeed, the very best

For additional information on the

classification and ranking of

|

click to continue to reading Exploring Burgundy - a 5-part mini series return to the Article Index |

|

Tyler Philp is a member of the Wine Writers' Circle of Canada Please direct inquires for writing services to: info@tylerphilp.com |

|

| Copyright © 2013 Tyler Philp

prior permission required for duplication of material |

|